In 1972, enthusiasm for the Equal Rights Amendment was the highest it had ever been. After sitting on the backburner of Congress for five decades, the amendment, first proposed by suffragist leader Alice Paul in 1923, had finally been approved by the U.S. Senate on March 22, 1972. The next step in the process was to get three-fourths (38) of all state legislatures to ratify it to enter the Constitution. At the heart of the ERA was the following text, meant to secure equal rights for all women: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Within a year of its approval, the ERA swept through 30 state legislatures, with only eight more to go. Enthusiasm for the amendment was so high, in fact, that Hawaii ratified it on the same day as the Senate. Likewise, it received widespread bipartisan support, garnering the approval of presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and both major political parties. It looked as though all the hard work of the women’s movement was about to be realized, that women would officially have equal rights constitutionally recognized.

But in an unforeseen turn of events, progress came to a near-grinding halt by the middle of 1973. When the ERA passed the Senate, it was attached with a seven-year ratification deadline, meaning that 38 state legislatures had to ratify it by March 22, 1979. But as the months went by, an extraordinary backlash campaign was launched against the ERA. It was so effective that by the summer of 1978, over six years after the amendment was approved by the Senate, ERA proponents found themselves three states short of ratification. With momentum behind the amendment nearly depleted, ERA activists were in dire need of additional time to secure the remaining votes.

But to do that, they had to confront one of the most influential oppositional campaigns in American history—one that forever changed the course of the women’s movement and the public’s relationship to feminism for the remainder of the century.

The Backlash to the Equal Rights Amendment

In September 1972, an organization called “STOP ERA” (an acronym for Stop Taking Our Privileges), launched a nationwide opposition movement to fight ratification of the ERA. The group's leader, conservative activist and author Phyllis Schlafly, claimed that if the ERA was ratified, mothers and working women would lose “the status of special privilege.” [1] It would “abolish a woman’s right to child support” and “absolutely and positively make women subject to the draft,” she declared. [2] As the anti-ERA movement progressed, Schlafly also repeatedly warned traditionalist audiences that the ERA would give women a constitutional right to abortion and legalize same-sex marriages and adoptions. [3]

Before she became the figurehead of the anti-ERA movement, Schlafly had a long history of political campaigning in Illinois. She was best known for her book A Choice Not an Echo in support of Republican Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign. The book sold over three million copies and helped establish her name as a conservative heroine of the right-wing of the Republican Party. [4] She later launched the Phyllis Schlafly Report newsletter in 1967, where she wrote about Cold War national security, communism, and free enterprise, and which by 1977 had a circulation of nearly 30,000. [5]

Schlafly’s anti-ERA campaign was motivated by a combination of traditionalist, Christian, anticommunist, and conservative beliefs about gender roles, sex, and the family in American society. She believed the women’s liberation movement was a “deadly poison” whose proponents were “waging a total assault on the family, on marriage, and on children.” [6] In contrast, she upheld the values of “our Judeo-Christian civilization,” which viewed men and women as having personal and moral obligations inherent to one’s sex. [7]

By the end of 1973, the STOP ERA campaign had thrown a massive wrench in the feminist movement and the ERA’s march through state legislatures. Whereas eight states ratified the amendment in 1973, only three states did in 1974. The following year, only one state ratified the amendment. In 1976, the number of new states was zero. And, in an extraordinary move, by July 1978, four states which had earlier approved the amendment (Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, and Kentucky) decided to rescind their ratification, a controversial decision that some questioned was legally possible.

With the 1979 deadline fast approaching, ratification was no longer guaranteed. The mass mobilization of conservative women forced a hard stop on the ERA. “No one anticipated the dimensions of the opposition that would develop,” wrote a commentator in the Baltimore Sun. [8] Judy Carter, the daughter-in-law of President Jimmy Carter and an ERA advocate, also expressed her fears for the amendment’s chances. [9] And by March 1978, the Sun reported that “ERA supporters have all but given up hope that the amendment will be ratified this year.” [10]

Extending the Deadline

With three more states still needed for passage (or more if the decisions to rescind by Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, and Kentucky were upheld), pro-ERA activists and organizations were in a race against time. To save the amendment, proponents began to push for an extension to the deadline in the fall of 1977. [11] In February of the following year, the National Organization for Women announced that it would launch a “major drive” to win a congressional extension for the ratification deadline. [12] But President Carter, who had qualms with the women’s movements’ positions on abortion and gay rights, wasn’t in a rush to act. [13] And Congress was slow to budge.

It wasn’t until May 17 when Indiana Senator Birch Bayh introduced a resolution in the House Judiciary Subcommittee to extend the deadline by seven additional years. [14] The measure was instantly met with controversy. By 1978, no constitutional amendment containing a ratification deadline took more than four years to be ratified. [15] Many viewed an extension as setting a bad precedent, with one Arizona Rep. stating, “[w]hat would you think of a football coach who demanded a fifth quarter because his team was behind?” [16] Eleanor Smeal, president of NOW, stated that refusal to extend the deadline risked “setting back the clock on women’s rights.” [17]

Finally, on June 5, 1978, the ERA got its first big break. Sen. Bayh’s measure narrowly passed the subcommittee by a vote of 4-3, upon which “Hundreds of ERA supporters who had crowded into the committee room broke into loud applause,” the Baltimore Sun reported. [18] And yet, the chances that the full committee would approve it were slim: “50-50,” guessed one representative. [19]

But proponents weren’t going to wait out congressional bickering. They wanted to show Congress that the ERA wasn’t dead: “The vitality of the amendment is very much alive,” said NOW Vice President Arlie Scott. [20] “We must get the ERA approved, even if it means taking to the streets,” said another proponent. [21]

The “largest parade for feminism in history”

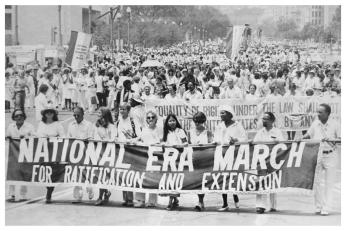

And take to the streets they did. Just after the July 4th holiday, supporters from across the country flocked to Washington for a march in support of extending the deadline for states to ratify the ERA.

“It’s gangbusters here today,” a NOW volunteer told the Evening Star on July 8. [22] The main event wasn’t until the following day, but already a flood of demonstrators had overwhelmed NOW headquarters, seeking information about places to stay. “I came because I wanted to be part of history,” said one activist from California. [23]

Across the District, activists booked hotels and were housed by friends and volunteers. “In some houses, we have 30 to 40 people staying,” said one NOW chairman. [24] Helen Helfer, a District resident, said she had “about 10 people staying at my house,” and “arranged for other accommodations all over my block.” [25] Event organizers also chartered more than 400 buses to bring supporters to the march, and NOW estimated that between 10,000 and 20,000 demonstrators would show up for the event. [26] Additionally, more than 325 organizations sponsored the demonstration, including “Religious groups, labor unions, civil rights organizations,” and “educational groups,” said NOW President Smeal. [27] “I just think this is going to be the most important civil rights march of the decade,” said Helfer. [28]

And on Sunday, July 9, with the temperature nearing the muggy mid-90s, tens of thousands of women, children, and men gathered on the National Mall for what would be declared the “largest parade for feminism in history” at the time. [29]

Hoisted across the grassy park were banners of gold, purple, and white, marking designated rallying points for the hundreds of delegations. The crowd, whose participants arrived from all corners of the country by airplane, train, bus, and car caravans, looked at one another with a staggered gaze, overwhelmed at the size of the gathered assembly. [30]

March organizers at first suggested the rally was 35,000 strong, but later in the day revised it to 90,000. [31] The U.S. Park Police commander placed the tally between 90,000 to 100,000 based on “years of experience.” [32] Other police estimates held out a range of 40,000 to 55,000. [33] What was clear, however, was that it was a colossal rally, and the demonstrators could feel it.

At half-past noon, with marchers lined up on Constitution Avenue, a girl scout carrying an American flag began the day’s procession. Marching behind her, the D.C. Columbian Band rolled out a step-lively beat, and a trolley packed with elderly suffragettes shouted, “we’re here to stay, and ERA won’t go away.” [34] Brimming with energy and euphoria, the demonstrators marched toward Capitol Hill.

With ecstatic enthusiasm, demonstrators sang and chanted all the way up Constitution Avenue. The chant most heard that day was “ERA now!” [35] At other times they exclaimed, “One two three four, we need three more (three more states to ratify), five six seven eight, Congress must extend the date!” [36]

Many of the marchers dressed in all white in a gesture to their suffragette foremothers, who, 65 years earlier—and staged by Alice Paul—conducted their own march down Pennsylvania Avenue. On that day in 1913, the women were forced to stop their rally due to the violence and disorder of the male opposition. In remembrance of the march, the 1978 demonstrators “struck a large bell for a note of mournful remembrance.” [37] July 9 also marked the one-year anniversary of Paul’s passing. Many of the marchers purchased Alice Paul buttons and pinned them to their white attire. [38] Some demonstrators also wore an ERA sash around their torsos.

The demonstrators came from all walks of life, each with their own reason for attending. “I was born a feminist,” said Marcia Karklin of Connecticut. “I came out of the womb with a clenched fist at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Providence, R.I.” [39] 74-year-old Nan Wood, who was president of her own Chicago-based electronics firm, exclaimed from her wheelchair: “I’ve been a feminist since I was born in 1903.” [40] One woman even named her daughter Era in honor of the ERA. [41] And among the New Jersey delegation, a sign was spotted that read, “Jesus Was A Feminist.” [42]

The marchers also had varying political outlooks. One activist called America’s federalist governing system “archaic,” and instead proposed “a national referendum” as an easier way to change the Constitution. [43] A member of the Workers World Party told the Evening Star that while the group supports the ERA, “we’re trying to put it in a class perspective.” [44] Not even the middle-class marchers “benefit under capitalism,” she said. Eileen Boris, reflecting on her participation in the march decades later, stated that while she was there to make history, she was not “a dedicated campaigner for the ERA.” She clarified that as a “socialist feminist, I understood that constitutional equality with men under capitalism would leave intact structures of class and race privilege between women.” [45]

Among the small minority of Black marchers was Gloria Ridley, a 35-year-old nursing teacher at the University of the District of Columbia. The lack of Black representation among the marchers made an impression on her, but it didn’t damper her spirits. Black women, she suggested, were already ahead of the game compared to whites in the fight for women’s liberation. “In essence,” she said, “we’ve been liberated for so long by necessity.” [46]

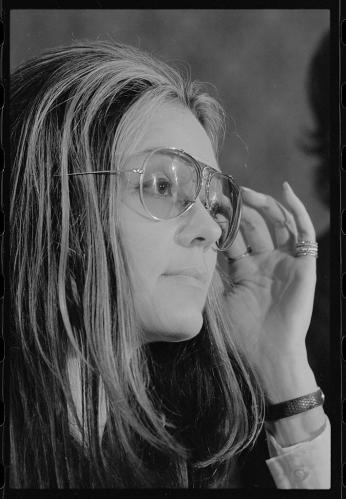

According to the New York Times, “it took nearly three hours for the crowd to march up Constitution Avenue to the grounds below the Capitol steps.” Once there, the crowd was to hear speeches from NOW President Eleanor Smeal, Chief of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Eleanor Holmes Norton, President Carter’s special assistant Margaret Constanza, and three members of Congress, including Reps. Elizabeth Holtzman, Barbara Mikulski, and Margaret Heckler. [47] Other icons of the women’s movement also attended the parade, including author Betty Friedan, Ms. magazine founder Gloria Steinem, and feminist leader Bella Abzug. [48] Actresses Ester Rolle and Marlo Thomas also made an appearance. “It’s an incredible turnout,” said Friedan, who helped launch the second-wave feminist movement with her 1963 bestseller The Feminine Mystique. [49]

Unfortunately, for some elderly marchers, as the day went on, they began to suffer from heat prostration. “I can’t tell you how many, but we’ve been carrying them off in a steady stream,” said the Deputy Chief of the Capitol Hill Police. [50]

With the July sun blazing down on the demonstrators, Rep. Holtzman, a Democrat from New York spoke to the thousands of activists gathered around the west steps of the Capitol building. She reminded the crowd of the significance of that day, their purpose, and the future they wanted to see: “This is an important day because American women are here in person to tell Congress we will no longer tolerate second-class citizenship. E.R.A. is the fulfillment of the American dream, not a threat.” [51]

Among the other highlights was a line from Eleanor Smeal, who made explicit what was at risk for women if the ERA failed: “What is at stake is constitutionality for women in this century, whether women will continue to earn only 57 percent of what men earn and whether women will be forever relegated to the dependence which low wages and low status impose.” [52] She also recognized the movement’s arch-enemy, shouting: “Phyllis Schlafly, eat your heart out!” [53]

Over at the Lincoln Memorial, 200 ERA opponents held a prayer meeting to protest the extension parade. [54] Schlafly was expected to show up with them, but never arrived. [55] She instead appeared in a TV debate earlier in the day and called the pro-ERA demonstrators “a combination of Federal employees and radicals and lesbians” seeking “to get this illegal extension of time.” [56]

Back on the Mall, Gloria Steinem spoke to the women in the crowd and warned of what was coming if Congress failed to act. “The lawful and peaceful stage of our revolution may be over,” Steinem said. “It’s up to the legislators. We can become radical, if they force us. If they continue to interfere with the ratification of the ERA, they will find every form of civil disobedience possible in every state of the country.” [57] She concluded, to an uproar of applause: “We are the women our parents warned us about, and we’re proud.”

As the day’s fanfare came to an end, organizers wrapped up with a celebration at the D.C. Armory arena from 8 p.m. to midnight. [58] Leaders of the extension drive promised to flood the offices of virtually all members of Congress to continue their lobbying effort. [59]

Winning the Extension

Eight days after the march, the House Judiciary Committee voted to extend the ratification deadline until June 30, 1982. Although it was not the original seven-year extension introduced by Sen. Bayh, it was a compromise that ERA supporters were willing to accept. Feminist leaders who were present in the committee room “erupted in loud applause and shots as the extension was passed.” [60] And on October 20, 1978, President Carter signed the resolution in the Oval Office. ERA supporters won their extension.

As it turned out, however, the extension would not lead to ultimate victory. Despite efforts by pro-ERA activists to win three more states, by the time June 30, 1982, rolled around, proponents still couldn’t get the 38 necessary states to ratify the amendment.

A week before the 1982 deadline, leading proponents of the ERA officially conceded defeat. “It is an outrage,” an exasperated Smeal told the press, “that in 1982 this nation could proclaim that women are not equal.” [61] At the same time, she vowed to continue the struggle – but only after the political landscape changed. [62] “We will not again seriously pursue the ERA until we’ve made a major dent in changing the composition of Congress as well as the state legislatures,” said Smeal. [63]

Forty years later, the ERA has yet to be ratified.

Henry Kokkeler is a recent graduate of Washington State University and earned his bachelor's degrees in history and political science. He has lived in northern Virginia since childhood and hopes to share his love for historical storytelling and to stir passions that only a deep connection with the past can excite.